|

PEOPLE AND POLITICS BY MOHAMMED HARUNA A (Brief) History of Nigeria’s Census

Nigeria’s first census since 1991 started yesterday. It may turn out to be the most controversial since the first nationwide census in Nigeria in 1921. Before the 1921 census there had been headcounts in the Lagos colony beginning from 1866. There were others in the same colony in 1871, 1881 and 1901. The next one in 1911 covered the amalgamated Lagos colony and the Southern Protectorate as one entity. It put the protectorate’s population at 7,858,689. In the same year there was a separate census in the Northern Protectorate. It put its population at 8,115,981. Following the amalgamation of the two protectorates in 1914, the colonial government passed the Census Ordinance in 1917, paving the way for the first nationwide census in 1921.

Thereafter, census became a ten yearly affair until independence in 1960. However, there was none in 1941 because of World War II fought between 1939 and 1945.

The last census before independence was held between 1951 and 1953. It put the North at 55.4% of Nigeria’s population and was used as a basis for allocating parliamentary seats at the centre among the then three regions of the federation, i.e. North, West and East. This invariably led to the politicization of census, a politicization that seems to have intensified with each subsequent census.

Not surprisingly the first post-independence census in 1962/63 was very controversial. The first count in 1962 was cancelled. The recount in 1963 was rejected by the East who’s Premier, Mr. Michael Okpara, dismissed it as worse than useless and headed for the courts for redress. Okpara’s grouse was understandable; every census before then had put the mainly Igbo East second to the mainly Hausa/Fulani North. This time the East reversed positions with the mainly Yoruba West.

The East lost its court case on the technical ground that the Supreme Court – at least that was what it said – lacked the jurisdiction to hear the case. In the end, the figures became official even though the headcount was regarded as less reliable than the previous one of 1951/53.

The next headcount came in 1973. It was, and still is, widely regarded as the most controversial to date. Like all previous census, it put the North ahead of the South. Predictably, it provoked angry rejection from Chief Obafemi Awolowo and from even some members of the census board including its chairman, the late Sir Adetokunbo Ademola, a former Chief Justice of the Federation. The controversy it generated apparently made General Yakubu Gowon, then Head of State, to dither about publishing the final figures. He was ousted by General Murtala Mohammed in 1975. The new head of state promptly cancelled the result.

The next headcount should have held in 1983. The civilian government of President Shehu Shagari which came to power in 1979 did indeed appoint a census board in 1981 under the late Alhaji Abdulrahman Okene. However, for some inexplicable reason, it did little besides. Shagari’s sack by the military in 1983 put paid to any plans his government had to conduct a census.

In 1988, the military took the bull by the horn and fixed 1991 for Nigeria’s first census since the failed 1973 exercise. That year, military president, General Ibrahim Babangida, appointed a census board under Alhaji Shehu Ahmadu Musa, Makama Nupe with a brief to conduct a successful census in three years and with fairly generous resources to back the brief.

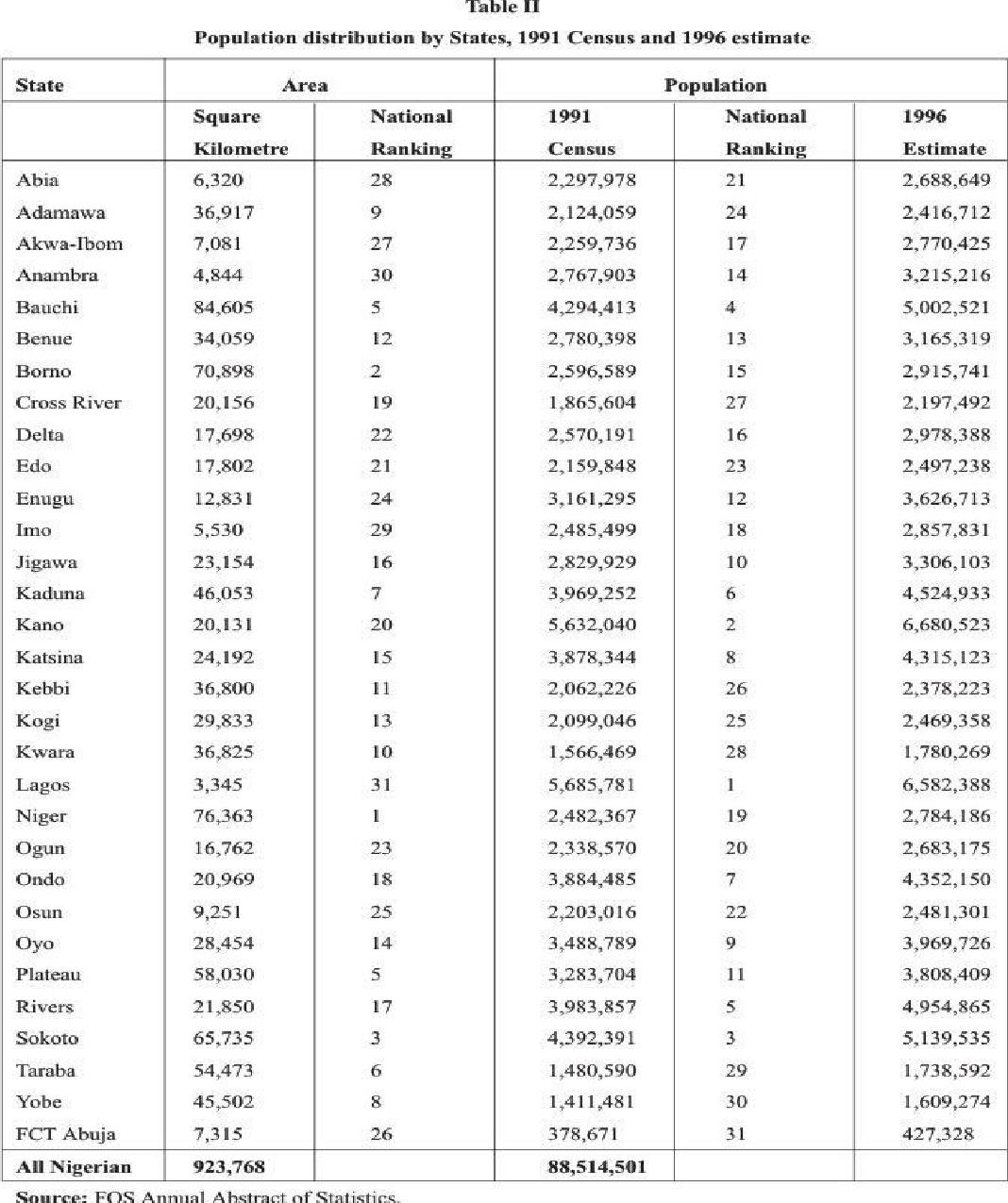

By most accounts the Makama met the nation’s expectations. Not everyone was of course happy with the results. Individuals like the late Chief Bola Ige and institutions like The Guardian rejected it, mostly on the spurious grounds that the less densely populated North cannot be more populated than the South, as the census result once more showed (see Table II).

However, even among leading Southerners, there was widespread acceptance of the results. Such leaders from the South like the chairman of the failed 1973 census, Justice Ademola, Professor Wole Soyinka, the Nobel Literature laureate, Professor Sam Aluko, one-time economic adviser to Chief Awolowo as Western premier, and Chief Omololu Olunloyo, one-time governor of the old Oyo State, all of them praised the conduct of the exercise as the best since census started in Nigeria.

Justice Ademola for example, said in The Guardian of March 2, 1992, that the 1991 results was a vindication of his rejection of the 1973 exercise. Similarly, Professor Aluko said in the Sunday Sketch of March 21, 1992 that the results tallied with what had always been his estimate of Nigeria’s population.

In spite of the less than universal acceptance of the 1991 exercise, it is today the official figure of Nigeria’s population and has been the basis of all the country’s demographic projections. Certainly that headcount has been the least controversial since 1953.

As we start the current headcount, the fear is that it may provoke greater controversy than even that of 1973. Actually it had been mired in controversy even before it started. And the single biggest culprit is the administration of President Obasanjo itself. The single biggest source of this controversy has been the administration’s politicization of the National Identity Card project, which, incidentally, General Obasanjo himself started in 1976 as a purely technical project. This was in his first coming as military head of state.

Apparently pandering to the wishes of Afenifere for a reversal of the demographic configuration of the country that had consistently put the North ahead of the South – Afenifere’s leader, Chief Abraham Adesanya, had once charged that the North counted its goats, cattle and sheep among its population - the president unwisely insisted on making the possession of the National Identity Card as a condition for voting in the 2003 elections. The assumption among Southern politicians was that a national ID card exercise would, once and for all, expose the Northern numerical superiority over the South as a colonial fraud.

The North’s resistance to the exercise on the grounds that there was insufficient time to conduct a thorough and reliable exercise before the elections of 2003 especially given the vast expanse of the region – at 730,885 square kilometers the region is nearly four times the size of the South - and that, in any case, it was wrong in principle to tie the vote to the possession of an ID card, seemed to have made the Southern politicians, those of Afenifere in particular, even more implacable in their assumption.

Not surprisingly as late as the middle of 2002, President Obasanjo was still insistent on linking the possession of an ID card to the vote. Precisely on July 16, 2002 he told a joint meeting of the INEC, the Department of National Civil Registration (DNCR) in charge of the ID card project and the National Population Commission that the possession of the ID card was a condition for voting. In the end the President dropped his insistence partly because INEC quietly objected to it on the ground that it violated the electoral law and the Constitution. The main reason for dropping the condition, however, was that government came to realize that it could simply not provide very adult with an ID card before the 2003 elections. More than four years after the ID card controversy broke out, most Nigerians, including this writer, are yet to get the ID card.

Wise counsel eventually prevailed and the exercise went ahead without tying the ID card to the vote. The results were declared by the Ministry of Internal Affairs in May 2003. As with the census exercises before it, it put the North ahead of the South (see Table I).

Source: Ministry of Internal Affairs and INEC

Strangely the figures were greeted by a very thunderous silence from critics of the country’s demographic configuration.

The inexcusable mixing up of the ID card project with census and with elections was not the only source of the difficulties that have faced the current census. It was, however the main source, not least because it led to the concentration of resources on the ID card project at the expense of adequate preparation for a census. For example in 2002 the president expropriated about 25 billion Naira for the project against the objection of the National Assembly at a time he allocated only 3 million Naira to agriculture, the mainstay of the country’s economy.

Again probably because of this mix-up, the census exercise was twice postponed first from 2001 and then from November last year. The mix-up also heightened existing ethnic and sectarian recriminations over the demographic composition of the country.

Not surprisingly as we start the exercise this week there are threats of boycott from religious organizations like the Christian Association of Nigeria, CAN, and from socio-political organizations like Ohaneze and Afenifere, that have objected to the removal of questions on religious and ethnic affiliations from the census questionnaire.

These recriminations apparently led The Guardian to suggest the postponement of the census in its editorial of February 26. These recriminations apart, the newspaper argued, there is the negative impact of President Obasanjo’s third term agenda on the credibility of the exercise.

As we enter the second day of the exercise today, it is obvious that The Guardian’s counsel has fallen on deaf ears, not least because it has apparently come rather late in the day. Perhaps the authorities were right to take a chance and go ahead with the exercise since there is no guarantee that postponing it till after 2007 will make it any more acceptable. If the ID card project which the South insisted upon at a time a Southerner was the president and a fellow Southerner, the late Chief Sunday Afolabi, was Minister of Internal Affairs and another Southerner, the late Mr. Deji Omotade who was in charge of the DNRC, could not, once and for all, settle the main issue of contention in our census – i.e. the numerical superiority of the North over the south – it is difficult to see how postponing the current exercise can make any serious difference.

Since going forward with the census is probably no worse than postponing it, especially having spent so much time and money in preparing for it, it is just as well government decided to get on with it. Who knows, some miracle may happen along the way and make it more acceptable than even the last one in 1991. In any case going ahead will invariably provide one more lesson on how to conduct a more acceptable census in future.

|